Translating Zappa in Moscow

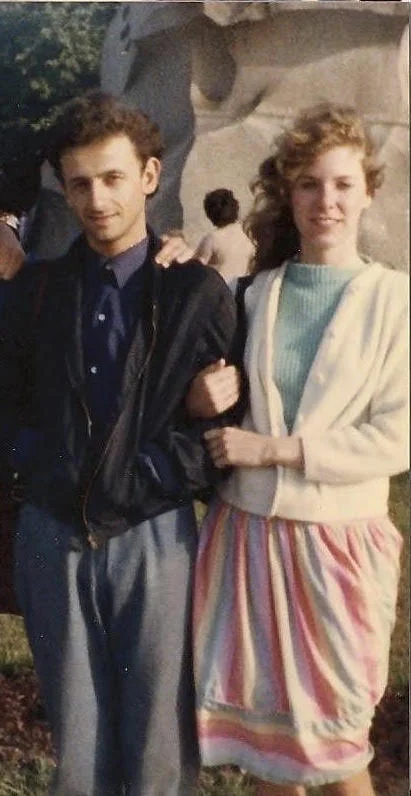

With Dima in Leningrad, Summer 1983

My attraction to languages began early. In my tween years, I volunteered summers at a camp for children with special needs. I watched, fascinated, as adults and deaf campers conversed, silently moving their fingers and lips. I wanted to communicate with the deaf children my age and took a course offered by the camp. I can still sign the alphabet, though most word gestures are long forgotten.

When Spanish was offered in high school, I enrolled. In college I studied Russian, French, and German, one class following another, a cup of coffee quickly sought during breaks to mentally transition between the worlds of da, oui, and ja. However, except for a year of night classes in Spanish with a teacher from Ecuador, I haven’t kept up with my studies since graduate school. I interpreted for church-sponsored Ukrainian immigrants when I first moved to Asheville, but now make the most of random opportunities speaking Russian with tourists passing through town.

Translating is a solitary art involving pencil and paper, grammar books and dictionaries, cross-outs and erasing, patience. You move between complicated, dynamic systems, your brain leaps from one language to the other, hunting for just the right word, and word order, to convey nuance. It’s akin to high-level math as you search for the value of the elusive x in the algebraic word problem. Have I captured the spirit of the original? Will a native speaker agree with my rendering?

Interpreting is live-action translating, heaven or hell, depending on your fluency and the subject matter. Technical subjects strain the brain of someone whose training was less practical, more literary. My experiences as an interpreter have been humbling. You quickly discover the limits of your vocabulary and grammar. I flash back to a Ukrainian stone mason who listened, frowning, as I struggled to explain the dimensions, angles, and materials for a stem wall he was expected to build for one of the church members. The mason and I defaulted to Runglish and hand gestures; we got through it, barely.

When Diane and I talked about memorable translating scenarios, I recalled the time in Moscow when, in the company of two Soviets, one of them wielding a rifle and pointing it at me and my two American friends, I was asked to translate Frank Zappa.

I was part of a Russian study group from Colgate University. We spent the summer of 1983 in Moscow, immersed in Russian classes at the Pushkin Institute. Our dorms were appalling--cockroaches ambled boldly over the toilet and across our bedsheets. Fruit and vegetables were a rarity in the cafeteria. Rumor spread that students who ate meat missed classes due to food poisoning. This was my summer of carbs, weight loss, and cigarettes. A hot, paranoid season in the Soviet Union. Andropov was in a coma, dying, our side trip to Kiev cancelled for security reasons, and the USSR embroiled in a protracted war in Afghanistan.

Although warned not to befriend Soviets, I was approached by a young man, Dima, who became my constant companion. Dima was smart, funny, fairly fluent in English, and desperate to hear about the world outside his country. He was poor, his clothes ill-fitting, his hair shaggy from a self-administered haircut, but he was an intellectual who rose above the indignities life threw at him. Though I had an American boyfriend and would not betray him, I was drawn to Dima and spent afternoons after classes walking with him around Moscow. He loved to talk about his country’s great writers. He showed me where the novelist Mikhail Bulgakov once lived; he described how the manuscript of Master and Margarita was almost lost.

Classmates Karen and Eric with me and Dima in Moscow, Summer 1983

Dima introduced me to his circle of friends. These meetings incurred great risk. Telephones were unplugged when we entered apartments as this was thought to deter government eavesdropping. At one gathering, Dima brought me into the kitchen to meet the host. A man stirred a large pot on the stove. I peered into the pot and asked what he was cooking. Poppy pods from Afghanistan. He was making a form of heroin. Gulag!, I thought, horrified. Discovery at this party, however innocent I would claim to be, would mean prison. Dima saw I was upset and tried to distract me with a flute--he called me his “Angel with the Flute” and pressed the instrument into my hands--but I shook my head, leaving immediately.

On the night of the Zappa incident, Dima invited me and two classmates to a friend’s apartment. We drank vodka, passed around a joint (my classmates and I declined, sharing Gulag fears) and discussed pop culture and current events. Dima’s friend became agitated when he brought up the war in Afghanistan. Only two years into our study of Russian, we students didn’t understand much of what he was saying. Our silence seemed to insult him. He left the room and came back with a rifle, pointing it at each of us, sneering the word “American.” I whispered to Dima that we needed to leave. He understood, but begged us to stay while he calmed his friend. The friend put on a Frank Zappa album and asked me, “What is he saying?” I’m pretty sure the song was “Bobby Brown (Goes Down)” and I had no idea what the Russian words were for the anatomical parts, sexual acts, and slang referenced in the song. Did the friend just want to see me struggle, blushing, not knowing what to do? Or did he really want my help interpreting Zappa’s bawdy lyrics? Between the rifle, the joint, and the increasingly uncomfortable vibe, it was time to go.

I remember leaving with my friends, Dima and his friend standing in the doorway of the apartment. It may have been this night that we Americans linked arms and walked side to side, singing the Monkees’ lyrics:

Here we come, walking down the street.

We get the funniest looks from everyone we meet.

Hey, hey, we're the monkees

And people say we monkey around,

But we're too busy singing

To put anybody down.

Dima followed our group to Leningrad when we’d finished our studies in Moscow. One evening Dima and I failed to get back to my hotel before the bridges went up to allow boats along the canals. We spent the endless white night on an impromptu walking tour of the city’s literary landmarks. He kissed me before we parted for the final time. He offered me his heart, which I gently refused. I don’t know what has become of him. I hope that he has had a good life, but sometimes that feels like American optimism, not bound by what may have befallen a man like him.