The mute translator

Deep emotions like love and hate transcend words, culture, origin. I fell in love with a foreigner and his language, Mandarin. He had a complex mind yet spoke very simple English. His brilliant ideas about solving real world problems using applied math required patient listening as he found words, circumvented concepts,and expressed part of his thinking in his native language to regain traction. I could sense his energy return as he spoke more fluidly, as if he needed a reminder of the value of his ideas. As he built word-by-word his command of English , I benefited from the exposure to his home language’s depth of meaning and core values. Mandarin’s simple structure holds a poetic power drawing on centuries old parables layered under the words.

Spoken Chinese is made up of monosyllabic words that seem to push against some friction in the mouth to sound like stones spitting out of a tumbler. To understand what is said, one must listen to the combinations and the musicality of the words. This isn’t easy, especially if you are tonally impaired like me. I have spent more than half my life learning Chinese and feel I could confidently perform well in a Beijing preschool class.

Part of this was a result of a marriage-saving decision to remain superficially capable when I agreed to have my in-laws come live with us. Typical of Chinese in-laws, they asserted opinions on all things and required respect and deference on many family decisions. My embracing the culture only went so far. I discovered that persistent ignorance dressed in smiles and kind gestures was the quickest end to a complaint or criticism. Ahh, ignorance was bliss, or at least a blissful disguise.

I do deeply love my in-laws and admire their courage to adapt to the US and also try to learn English. They also are amazing with my children always doting on them. All of my children are bilingual and able to give and receive loving words with their Chinese grandparents. ResidingLiving in the international district with many Chinese businesses who speak Mandarin has allowed them to live independently, happily. However, going to the hospital or a specialist requires me to step in as an advocate. We always request a translator to join us. I am not fluent in medical terminology and this is the type of translating you don’t want to get wrong. Even my former husband requests a translator. I have gone to the hospital or doctors with my in-laws dozens of times. On rare occasions, I have been asked to help out when the translator doesn’t show or somehow wasn’t ordered. I take no joy in these experiences. I reached my breaking point when I am dragooned into the OR to be on hand to help communicate to my father-in-law during eye surgery.

“Can you help him out?”

“I don’t know any medical terms and am really not very good.”

The translator was not coming. The anesthesiologist, who spoke Mandarin with my father-in-law just minutes before going in, assures me it will be fine. The surgery will be simple and short. My father-in-law will have a local anesthetic isolated to his eye. I feel buoyed by her presence. The surgeon further assures me all will be fine as this is a repeat surgery for my father-in-law who had burst the vessel on the other eye. I am reminded the surgery is urgent and we should not delay.

He concludes, “Let’s try and see how many we can do.”

I feel my spirit flee, as I rest my arm on Baba, my father-in-law’s, shin. This is one of those times I defer to others, believing they must know better than me. Listening to my gut just stirs needless worry. Still, I decide to ask the medical assistant one more time if they have any word on the translator. She tells me no.

The assistant hands me a gown and hairnet. I swirl in confusion but am reassured by the mandarin-speaking anesthesiologist’s presence.

On the table, my father-in-law lays flat, a mask covering his face except for one eye. The surgeon asks him, “Are you feeling ok?”

I speak up, asking him the same in Mandarin. I feel relief as i communicate back to surgeon from my designated seat at the end of the bed.

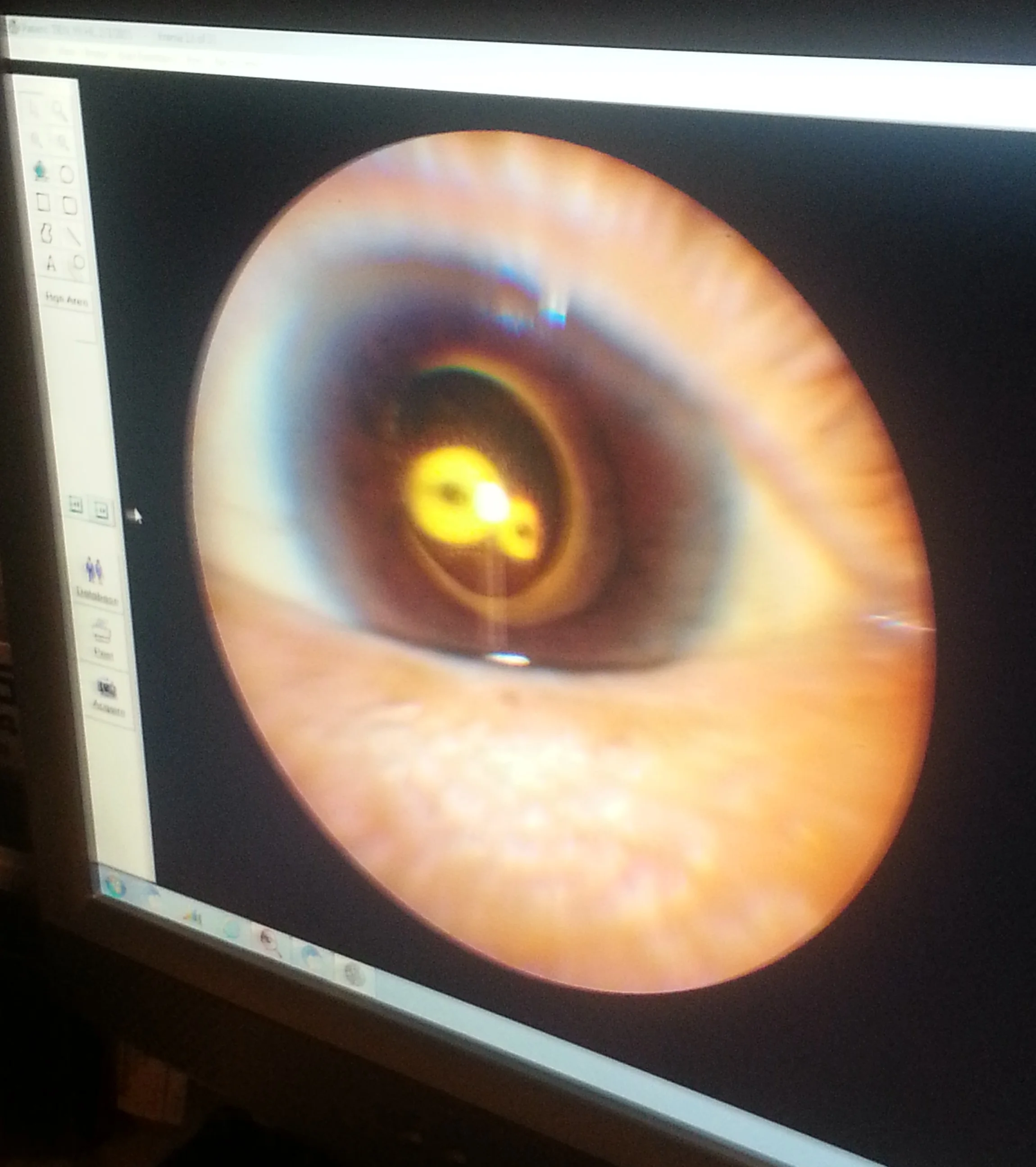

The surgeon stands at the head of the table. He wears specialized microscope eyeglasses and alternately looks down at my father-in-law’s eye, then up at a TV screen just off to the left. There a camera is mounted on a mechanical arm, positioned to capture my father-in-law’s right eyeball. In front of me, closer to the surgeon s a metal tray with many instruments that look like pens, and a few smaller tools that remind me of items I might have seen before at my dentist’s office. An assistant stands behind the tray, ready to hand the surgeon what he needs.

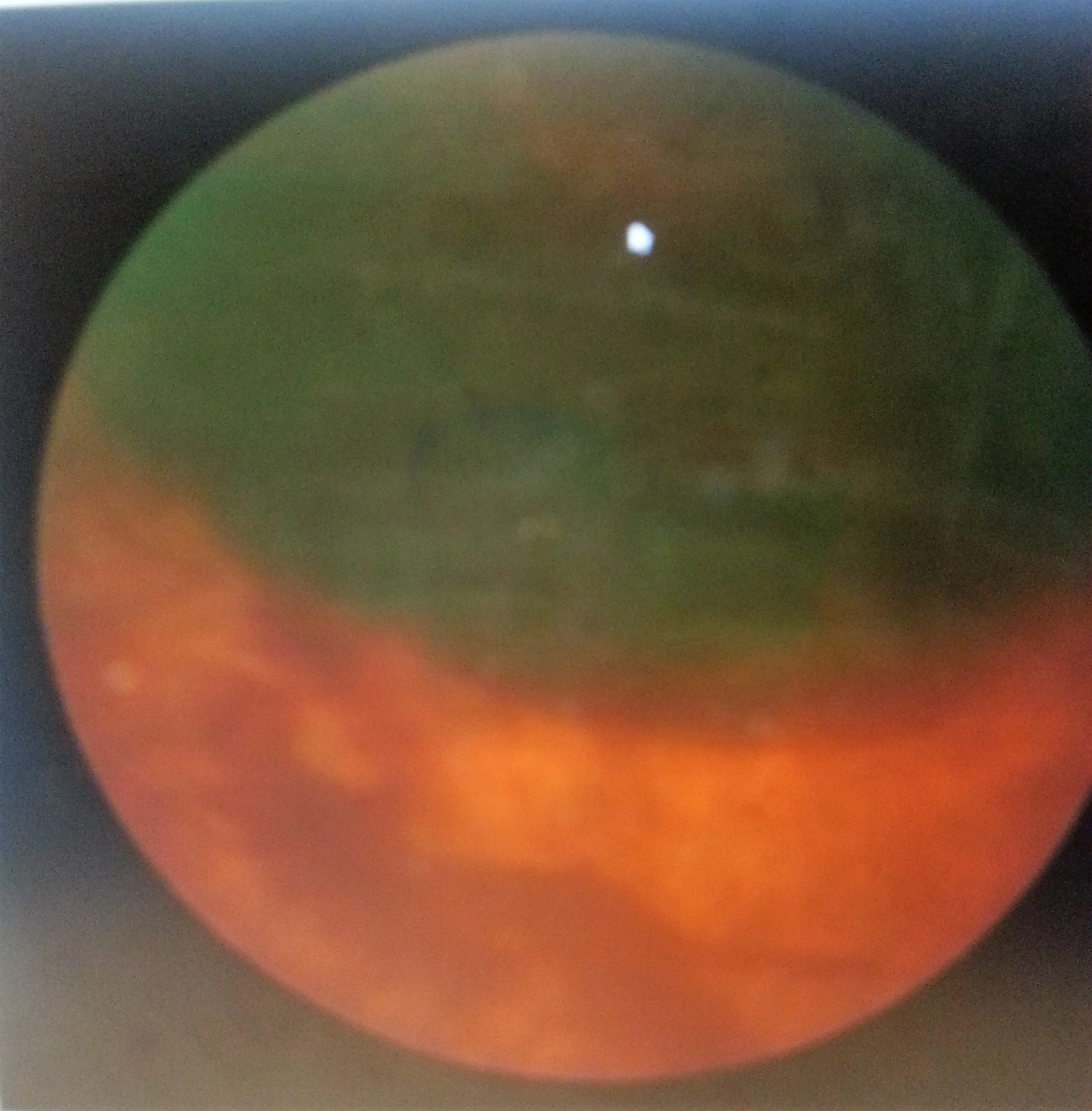

The doctor begins to operate. I observe my father-in-law’s eye on the TV. It resembles a planet photographed from the hubble telescope. I am transfixed. I watch the doctor delicately use microtweezers to remove what looks like a glistening clear gelatinous contact. I am caught up with the eye-hand precision as the surgeon looks at the eye and then to the screen.

“Mr Tien, Mr. Tien! Put your arm down!” The surgeon calls out.

I see the blue sheet covering my father-in-law begin to billow as he tries to lift his arms upward. Panic engulfs me. I drop my phone with my pre-loaded translation phrases. The surgeon holds his position as does the assistant while I spring forward to hold my father-in-law’s arms down. In my haste, I hit the metal tray sending it upward into the air. The assistant shouts for me to sit down.

The tray miraculously slaps back down into the tray holder. I can see and hear a few articles clank on the ground. I pray not his cornea.

“Move her away!” shouts the assistant.

The surgeon interjects, “Diane, sit closer to his feet.” I lift my hands off of my father-in-law as this new person clad in blue comes up behind me and places his blue gloved hands on my father-in-law's arms.

In an instant, I try to replay in my head what just happened. Did the surgeon’s instrument plunge into his eyeball? The assistant now retrieves something from a closet and said says to surgeon, “We have one.”

““One what?,” I wonder.” Oh, God. I feel sick and yet charged like a balloon after being scrubbed a scrubbing overon a young girl’s head of hair. I’m mentally torqued, I hold my arm on the shin of my father-in-law to keep anchored, repeating the words “Don’t move’ over and over, softer and softer. The second attendant lets go of my father-in-law’s arms, sensing the storm has passed. The surgeon carries on and I watch the screen for clues of permanent blindness.

When I’m dismissed, I get up to leave and see the Chinese anesthesiologist in the corner of the operating room.